Technofeudalism Part Two: The Troll Toll

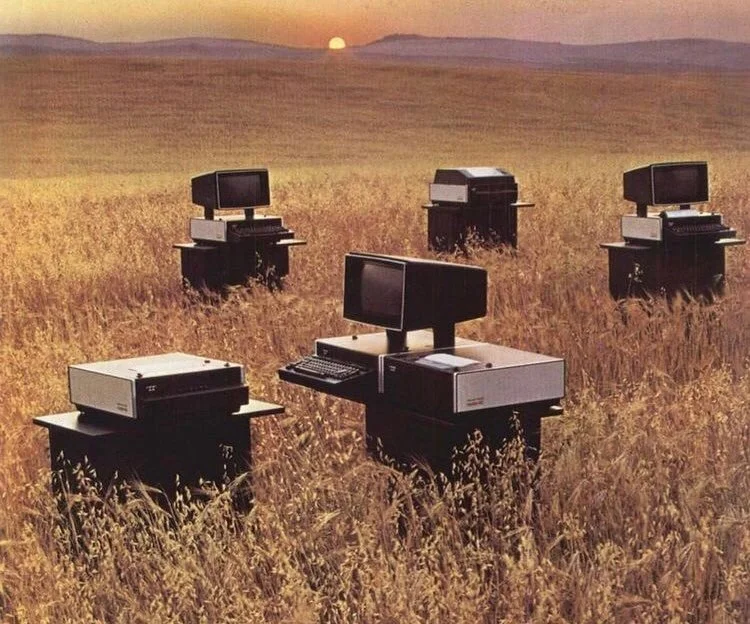

Introduction to the Digital Age and Shifting Economic Realities

The advent of the digital revolution has transcended mere technological advancement, fundamentally reshaping global economic and social structures. This transformation has given rise to novel power dynamics and intricate mechanisms of value extraction. The initial observations of changing economic realities, such as the fluctuating costs and dynamics within the sex work markets in Boston and Amsterdam, or the significant decrease in cab fares over two decades, serve as compelling empirical starting points. These seemingly disparate examples prompt a deeper investigation into the underlying systemic forces at play, moving beyond superficial explanations of traditional supply and demand to reveal profound structural shifts.

A handful of Big Tech companies have ascended to positions of unprecedented control and dominance, exerting significant influence over human thought and behavior. This pervasive control raises a critical question: is it an intentional design, or an unintended byproduct of a system that relentlessly encourages infinite growth and data accumulation? This inquiry sets the stage for a comprehensive examination of how individual attention is commodified and how pervasive monitoring systems operate within the digital sphere. The reduction in cab fares, for instance, is less about population collapse or labor shortages and more a manifestation of the disruptive intermediation and dynamic pricing models introduced by digital platforms like Uber and Lyft. Similarly, the evolution of the sex work market is intrinsically linked to how digital platforms facilitate client screening, communication, and introduce new forms of both autonomy and exploitation. These observed changes are not merely typical market fluctuations; they are symptomatic of a more fundamental, systemic transformation. The report aims to establish that the "how"—the mechanisms of digital platforms, algorithmic control, and data monetization—is as crucial as the "what"—the observed changes in wages or prices. By connecting these real-world phenomena to the theoretical underpinnings of techno-feudalism, the analysis demonstrates that these are not isolated incidents but manifestations of a new, evolving economic order.

This report formally introduces "Techno-feudalism" as a critical theoretical framework, primarily articulated by economist Yanis Varoufakis, for understanding the contemporary concentration of power and wealth in these tech giants. It also defines "Troll Toll" as a multifaceted concept representing the diverse, often subtle, mechanisms through which value is extracted and control is exercised within this evolving digital economy.

Techno-feudalism: A New Economic Order?

The concept of techno-feudalism, prominently advanced by Yanis Varoufakis, posits a radical reorientation of the global economic system, suggesting that traditional capitalism has "eaten itself" and morphed into a new, more exploitative form. Varoufakis argues that this is not merely a new phase of capitalism but a fundamentally different system where its traditional dynamics no longer govern economies. This "rupture" within capitalism, he contends, was precipitated by the emergence of a novel form of capital.

Yanis Varoufakis's Core Thesis

Varoufakis's central concept is "cloud capital," which he identifies as a mutated form of capital that has arisen over the last two decades, possessing significantly greater power than its industrial predecessors. A critical distinction of cloud capital is its mode of accumulation: unlike traditional capital goods such as ploughs, hammers, steam engines, or industrial robots, which necessitate waged labor for their production, cloud capital (exemplified by platforms like Twitter, TikTok, Uber, and Google) accumulates primarily through the unpaid activities of users, whom he terms "free laborers" or "cloud serfs". This represents a profound conceptual shift from the core tenets of industrial capitalism, where capital was primarily invested to produce tangible goods or deliver direct services. In the techno-feudal framework, the "product" becomes the manipulation and monetization of human behavior and attention, which then generates "cloud rent". This implies that the primary economic activity is no longer direct production for market exchange, but rather the cultivation of desire and the channeling of user activity within proprietary digital spaces. The "free labor" of users engaging with platforms directly increases the platform's capital stock, generating value without traditional wage compensation, which is a significant departure from capitalist labor relations.

In this new system, traditional competitive markets are increasingly supplanted by "digital platforms that resemble fiefdoms". Consequently, the primary mode of surplus extraction shifts from capitalist profit to "cloud rents". The owners of cloud capital, or "cloudalists," strategically invest vast sums to effectively dismantle both competitive markets and the pursuit of profit, replacing them with the extraction of cloud fees and rents. This rent, much like in historical feudalism, flows from privileged access to a scarce resource—not fertile land, but digital space and the data within it.

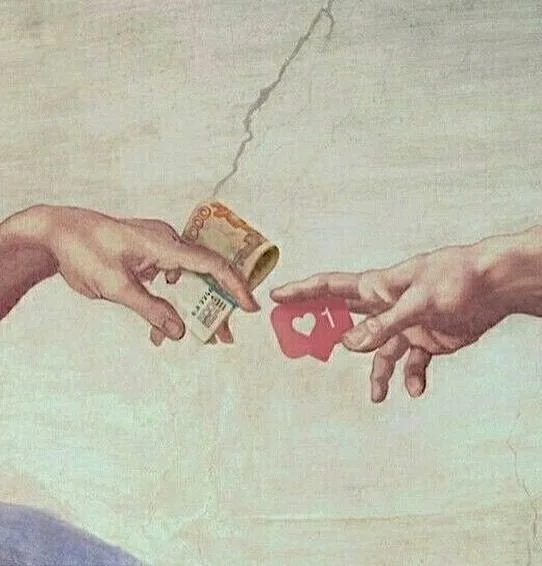

Varoufakis defines cloud capital not as a means of producing commodities, but as a "produced means of behavioural modification". Platforms are designed to train users to desire specific products or services, which the same algorithmic capital then sells to them. A key example is Amazon's Alexa: it is presented as a "free, pretend slave" that users interact with and train. In turn, Alexa learns user preferences, builds trust through recommendations, and ultimately modifies user behavior to encourage purchases from Amazon.com, with Jeff Bezos, the owner, retaining a significant portion of the price as "cloud rent". This contrasts sharply with commodified AI services like OpenAI's ChatGPT, which operate on a subscription model. This redefines the very nature of economic value creation in the digital age. It is no longer solely about selling a product or service; it is about controlling the desire for it, the attention directed towards it, and the path through which it is acquired. This mechanism effectively turns users into active, albeit often unwaged, contributors to the platform's capital accumulation.

As the digital world increasingly and forcibly overlaps with the real, we should be mindful of who owns these platforms and the costs they impose on us.

The perceived "freeness" of services offered by many Big Tech platforms (e.g., Google Search, Facebook, Amazon's Alexa) is often deceptive. The implicit "cost" is the surrender of personal data, attention, and ultimately, autonomy. The notion that platforms "enslave our minds" suggests that this "free" access comes at a profound, often hidden, cost to the individual. The historical analogy to feudalism, where serfs had limited choices despite the "protection" offered by their lords , becomes highly relevant. Users are "locked in" to platforms and their "choices" are increasingly limited or inconvenient , rendering the "free" service a sophisticated mechanism for control and rent extraction. By offering services "for free," these entities bypass traditional market mechanisms where consumers explicitly pay for goods or services. Instead, they create a system where user engagement, data, and attention become the primary currency. This cultivates a dependency that, while not enforced by physical coercion, is economically compelling. The perceived convenience and value of these "free" services mask a deeper system of control and value extraction, where users are not traditional customers but rather "cloud serfs" whose digital activities are the primary resource for platform accumulation. This makes the argument that modern users have "choices" less compelling when considering the systemic dependencies and the high switching costs created by platform dominance.

Varoufakis explicitly links the rapid rise of technofeudalism to the aftermath of the 2008 global financial crisis. He states that "insane sums of money that were supposed to re-float our economies after the crash of 2008 went to big tech instead". This massive influx of capital, channeled through financial institutions, funded the construction of "private cloud fiefdoms". This suggests a direct causal link where government-led financial interventions, intended to stabilize traditional economies and prevent collapse, inadvertently provided the fuel for the exponential growth of a new, potentially more exploitative, digital economic order. The bailouts and quantitative easing policies created an environment ripe for the accumulation of cloud capital, as these tech investments offered high returns in a low-demand economy. This highlights a critical macroeconomic dimension, indicating that the emergence of technofeudalism was not solely an organic evolution driven by technological innovation but was significantly accelerated and shaped by specific state-level financial policies. This implies a complex interplay between government action, financial markets, and technological development in forging the current digital power structures.

It is important to note that while Varoufakis's thesis is influential, it is also subject to academic debate. Critics argue that the phenomena he describes, such as rent extraction by tech companies and the global scale of their operations, are extensions or intensifications of capitalism, rather than a fundamentally new system. Some scholars contend that the term "technofeudalism" might obscure the continuity of capitalist relations, pointing out that tech companies still rely on wage labor, pursue profit maximization, and operate within market structures, albeit monopolistic ones. They also highlight that tech companies are owned by shareholders, not hereditary lords, and while they influence political systems, they do not replace state structures directly. These counter-arguments suggest that the current digital economy might be better understood as "platform capitalism" or "surveillance capitalism," representing a new phase of capital accumulation rather than a complete break from capitalism.

Historical Parallels and Analogies

Thank you to our new God Zuckerberg, for blessing us with likes—please, please, relieve me of my burdens in exchange, take everything of value I have.

Varoufakis and other thinkers draw a direct and striking parallel between medieval feudalism and the digital age. In this analogy, tech giants assume the role of modern feudal lords, while everyday internet users are likened to serfs. Just as medieval lords exercised dominion over land and the labor of their peasants, contemporary tech companies wield immense power over data and access to digital spaces.

The internet and its vast network of digital platforms are conceptualized as the new "land" or "cloud fiefdoms" of this era, controlled by a select few dominant entities such as Google, Amazon, and Meta. Users "congregate" within these fiefdoms, voluntarily contributing their labor and data, which then fuels the platforms' accumulation of capital. The relationship between tech giants and users or businesses mirrors the dependency of peasants on their lords. Businesses and workers must adhere to platform rules to generate income, akin to how medieval peasants relied on their lords for protection and access to land. The sheer volume of personal data collected and owned by tech companies grants them unprecedented power over users.

A critical loss highlighted by this analogy is the erosion of privacy. Before the advent of the "Troll Toll" era, privacy and anonymity were inherent in activities like using paper correspondence or public phone booths. Now, an individual's location, identity, and personal preferences are subject to constant monitoring and commodification. This historical comparison underscores the fundamental shift in individual autonomy and control over personal information in the digital age.

The "Troll Toll": Mechanisms of Value Extraction in the Digital Economy

The "Troll Toll" encapsulates the diverse, often subtle, mechanisms through which value is extracted and control is exercised within the evolving digital economy. This concept extends beyond explicit monetary fees to encompass various forms of rent extraction and friction imposed by dominant digital platforms.

Sources:

Capitalism is capitalism, not technofeudalism: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1468795X241269293

No, It’s Not Techno-Feudalism. It’s Still Capitalism: https://jacobin.com/2023/04/evgeny-morozov-critique-of-techno-feudalism-modes-of-production-capitalism

Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism: https://www.amazon.com/Technofeudalism-Killed-Capitalism-Yanis-Varoufakis/dp/1685891241